The Intruder, 2004

The everyday: what is most difficult to discover. In a first approximation the everyday is what we are first of all, and most often: at work, at leisure, awake, asleep, in the street, in private existence. The everyday, then, is ourselves, ordinarily. (…) Boredom is the everyday become manifest: as a consequence of having lost its essential–constitutive–trait of being ‘unperceived’. Thus the daily always sends us back to that inapparent and nonetheless unhidden part of existence: insignificant because always before what signifies it; silent, but with a silence that has already dissipated as soon as we keep still in order to hear it, and that we hear better in idle chatter, in that unspeaking speech that is the soft human murmuring in us and around us.

Maurice Blanchot, ‘Everyday speech’, 1969

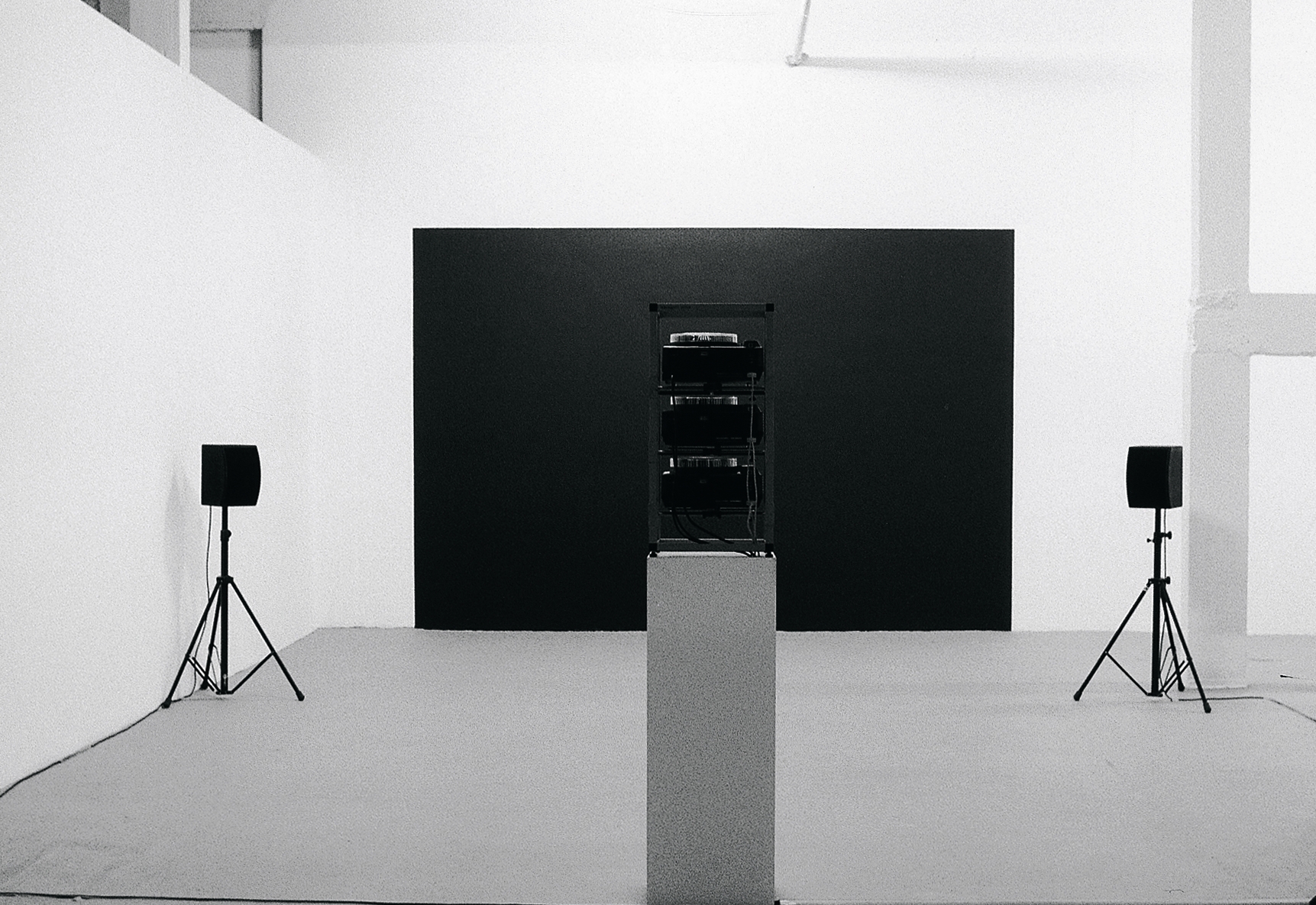

THE INTRUDER, an installation with slide projections and audio narration, is based on ‘L’Intruse’ (1890), Maurice Maeterlinck’s second play, which was performed for the first time in May 1891 in Paris (directed by Lugné-Poe) at a benefit event for the painter Paul Gauguin and the poet Paul Verlaine. This one-act play had achieved a cult status by the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century and it was translated in the most unimaginable languages, all over the world. It was staged by none other than Vsevolod Meyerhold in 1903 but also by Konstantin Stanislavsky, the father of ‘method acting’ in 1904.

Torfs has always felt strongly attracted to the early Maeterlinck plays, with their Beckett-like language.* In 2004, she invited Gila Walker to make a new translation of the French play into English**. Torfs reduced the text to its essence. She changed the gothic setting of the play into a villa with a modern interior – ‘the action takes place in modern times’*** – a strictly functional decor. She introduces the five archetypal characters while they are waiting in the living room of a modern villa facing a garden, on a Summer evening: the blind grandfather, his son, his son-in-law, his granddaughter and a maid-servant. Off-screen, the voices of five other actors accompany the slide photographs with theatrical intonation.

The slides are projected on a black projection surface, a radical and very suggestive conceptual choice, creating a eerie atmosphere. It could also be seen as a playful reference to ‘day for night’. Day for night, also known as ‘nuit américaine’ (American night), is the name of a cinematographic technique to simulate a night scene. Mainly intended to avoid costly night filming, outside scenes can instead be shot during the day, with special filters and under-exposed film to create the illusion of darkness or moonlight. The ‘filtered’ slide photographs that appear on Torfs’ black projection surface are also reminiscent of early photography and daguerrotypes, with different hues in the range of brown and bronze tones.

What we see is the ‘positioning of a family’, operating within a tightly confined space. Over and again the short, at times absurd dialogues return to the sensory perceptions of hearing and seeing. The father: ‘There’s an extraordinary silence.’ – The uncle: ‘That’s exactly what I don’t like about the country.’ Or: The father: ‘We can’t stay like this in the darkness.’ – The uncle: ‘Personally, I don’t mind talking in the dark.’ Torfs similarly subjects the viewers in the exhibition space to a strange rhythm of shifting impressions. Sometimes the slides are interrupted by intertitles; at other times obvious changes in position follow one another in the sequence; at times almost identical images are rapidly crossfaded, creating a sense of puppet-like motion. The anti-naturalistic delivery of the text by the British voice actors underscores the stylisation of the piece by Torfs and hence all the more clearly foregrounds the minimalistic structure of the one-act play. Nothing seems to happen, apart from waiting, on a long Summer evening. The wait itself, and through it consciousness of time, become one of the installation’s dramatic issues. ‘What are they waiting for? They do not know! They are waiting for someone to knock on the door, waiting for the light to fade out, waiting for Fear, waiting for Death. Do they speak? Yes! They speak a few words, breaking the silence for a moment, then they begin listening again. Leaving their sentences unfinished and their gestures interrupted. They listen, they wait. Perhaps she will not come? Oh! She will come. She always comes. It is late, maybe she will only come tomorrow. And the people gathered in the big room begin to smile and to hope. There is a knock on the door. And that is all; this is the whole of their lives, this is the whole of life.’ ****

- In 1985, while still a student, Torfs already made a radio play based on ‘L’Intruse’.

- the first new English translation since 1894

- opening sentence of the play

- quoted from Remy de Gourmont, ‘Le livre des masques’, 1896

- opening sentence of the play

- the first new English translation since 1894

This work was shown for the first time as a solo exhibition at Roomade in Brussels in 2004.