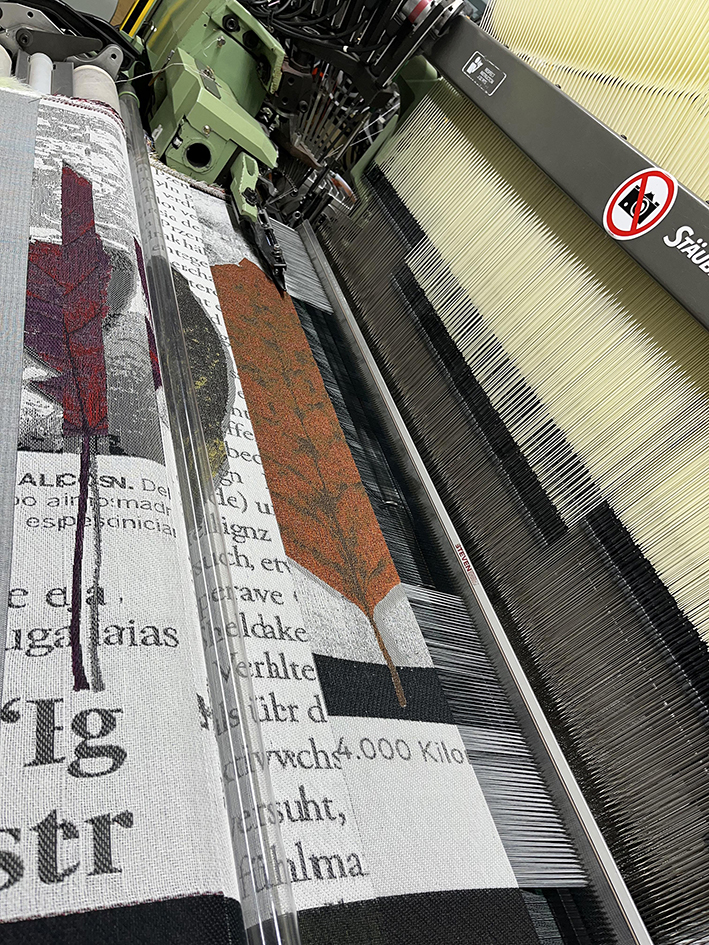

The Day You Where Thinking About the Sibyl While You Were Picking Autumn Leaves (in progress), 2020-2025

Even though my work is very visual, text has always played a major role in it, whether it is self-written text or pre-existing texts I reuse, often in the form of fragments or collages. It is no wonder then that I’m attracted to textile. The words text and textile are both derived from the Latin verb texere, meaning to weave. It implies that weaving preceded writing, and that the first writers saw themselves as weavers. In The Elements of Typographic Style (1992), Robert Bringhurst writes: ‘An ancient metaphor: Thought is a thread, and the raconteur is a spinner of yarns-but the true storyteller, the poet, is a weaver.’(1)

In that strange summer of 2020, when a virus had the entire world in its grip, I was reading Vergil’s Aeneas. In part three, my attention was caught by the following fragment: And when, (…), you draw near to the town of Cumae, the haunted lakes, and Avernus with its rustling woods, you will see an inspired prophetess, who deep in a rocky cave sings the Fates and entrusts to leaves signs and symbols. Whatever verses the maid has traced on leaves she arranged in order and stores away in the cave. These remain unmoved in their places and do not quit their rank; but when at the turn of a hinge a light breeze has stirred them, and the open door has scattered the tender foliage, never thereafter does she care to catch them, as they flutter in the rocky cave, nor to recover their places and unite the verses; inquirers depart no wiser than they came, and loathe the Sibyl’s seat. (2) Only enigmatic fragments remain of the Sibyl’s prophecies: disjecta membra, scattered leaves.

So it was surely no coincidence that I thought of the Sibyl of Cumae, the famous oracle who predicted the future on autumn leaves, when I spent four weeks collecting autumn leaves in my hometown of Brussels at the end of October 2020. It was a way to clear my mind after my solo exhibition at Bozar in Brussels was closed for the second time due to a government-imposed lockdown. The repetitive gesture of reaching for the ground to pick up a leaf, then laying it at home between newspaper pages (2) to dry: it brought rhythm to my life during that difficult period. When, after weeks, the leaves were finally dry, I made photographic images of a selection from this herbarium, as a basis for 28 textile designs, in which these photos were combined with short text notes that were cut out of a leaf of paper. These notes are anaphoric exercises in brevity, each of them starting with: ‘The day that’ or ‘The year that’. In these short notes, my thoughts circle around things that matter for me, small snippets I kept on polishing until I felt it was right.

More later, work in progress.

1. Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style, Hartley and Marks Publishers, 1992, p. 25

2. I dried them between daily bought (inter)national newspapers of that period in 2020, in six different languages (Dutch, French, English, German, Spanish and Italian) and a bi-monthly Dutch_language art newspaper.