Family Plot, 2009-2010

During a residency in Gotland (Sweden) in 2007, Ana Torfs stumbled upon the figure of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the famous Swedish “Father of Modern Taxonomy.” Before Linnaeus, many naturalists gave the species they described long and awkward Latin names, which could be changed at will. The need for a practicable naming system was intensified by the growing number of plants and animals that were being brought back to Europe from Africa, Asia, and the Americas in the 18th Century. Linnaeus introduced the systematic use of binomial nomenclature in Latin, giving plants and animals a generic name and a specific epithet. We owe the name of our species, Homo sapiens L. to Linnaeus, who published the term in 1758. Although he was not the only naturalist to use binomial names, he was the first to introduce this with consistency and precision in his magnum opus Species Plantarum (1753).

The more Torfs read about the history of the binomial classification system, the more she was fascinated. A passionate gardener herself, she decided to make a work starting from the official names of 25 very well chosen botanical species and the “naming story” behind them: The name Solandra grandiflora Sw. for example, was a tribute by Swedish botanist Olof Swartz to Linnaeus’ pupil Daniel Carlsson Solander, who moved to London in 1760, thus promoting the Linnean classification system in England.

In English, a “family plot” is a larger section of a cemetery, including burial plots for members of one family. Ana Torfs’ installation takes the form of a gallery of forefathers, consisting of fifty framed prints, with Carl Linnaeus as central figure. Linnaeus’ taxonomy often entailed the dedication of exotic plants to their — usually European — discoverers, commissioners, sponsors, or kings. One could describe this politics of naming as a form of “linguistic imperialism”, whence also the allusion to a conspiracy or storyline in the work’s title. It refers to the dark side of this “family plot”, the hegemonic exclusion of the Other, even in ostensibly objective disciplines such as botany.

This naming politics accompanied and promoted European global expansion and colonization (ignoring existing indigenous names, for example). “From Columbus to Humboldt the principle of attachment served to make the incommensurable seem commensurable. (…) Attachment allowed for the creation of an initial (if also sometimes troubling) familiarity. It also allowed the discoverer to make some measure of classification. Above all, it allowed him to name, and by naming, to take possession of what he had laid eyes on.”*

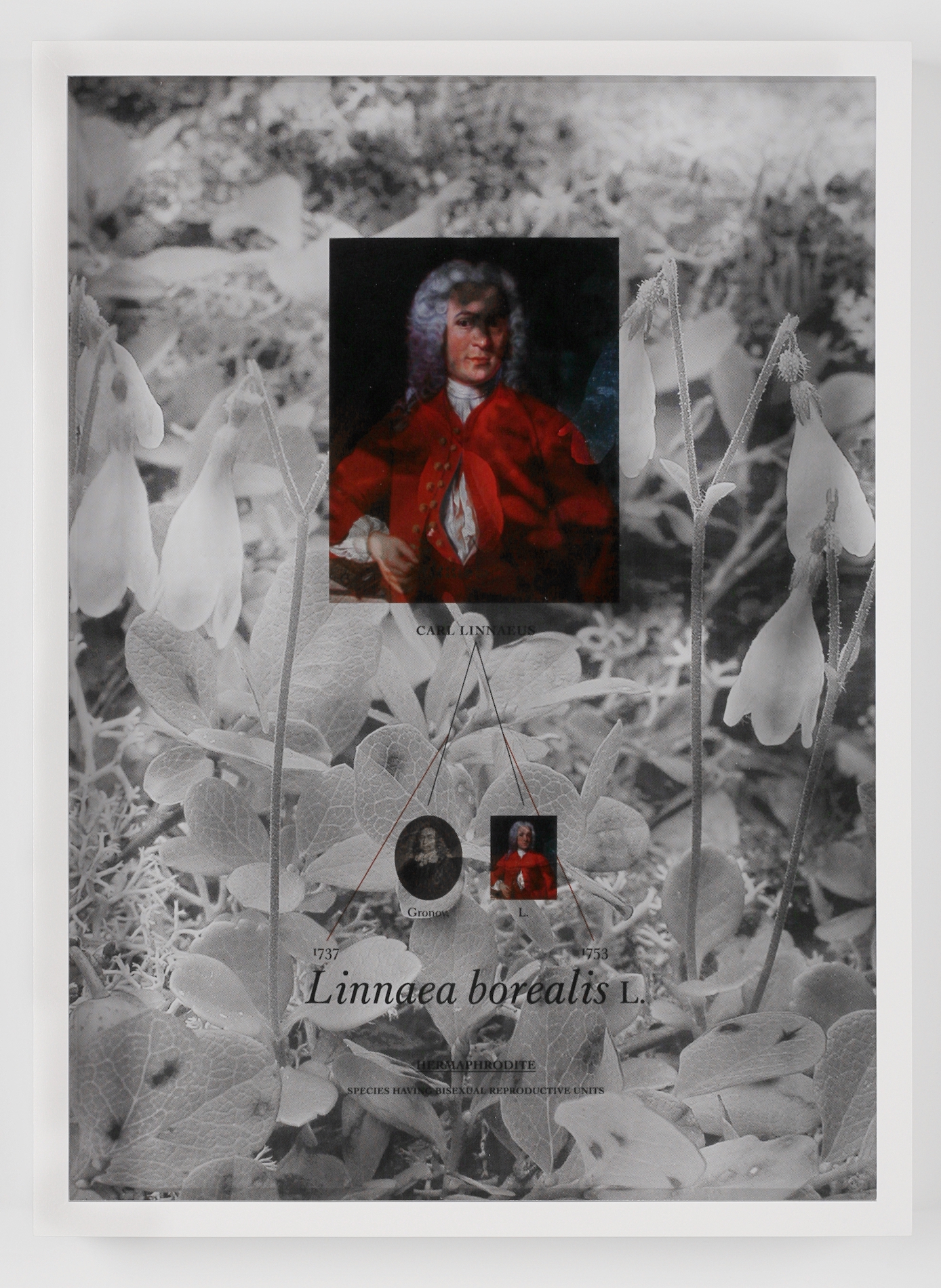

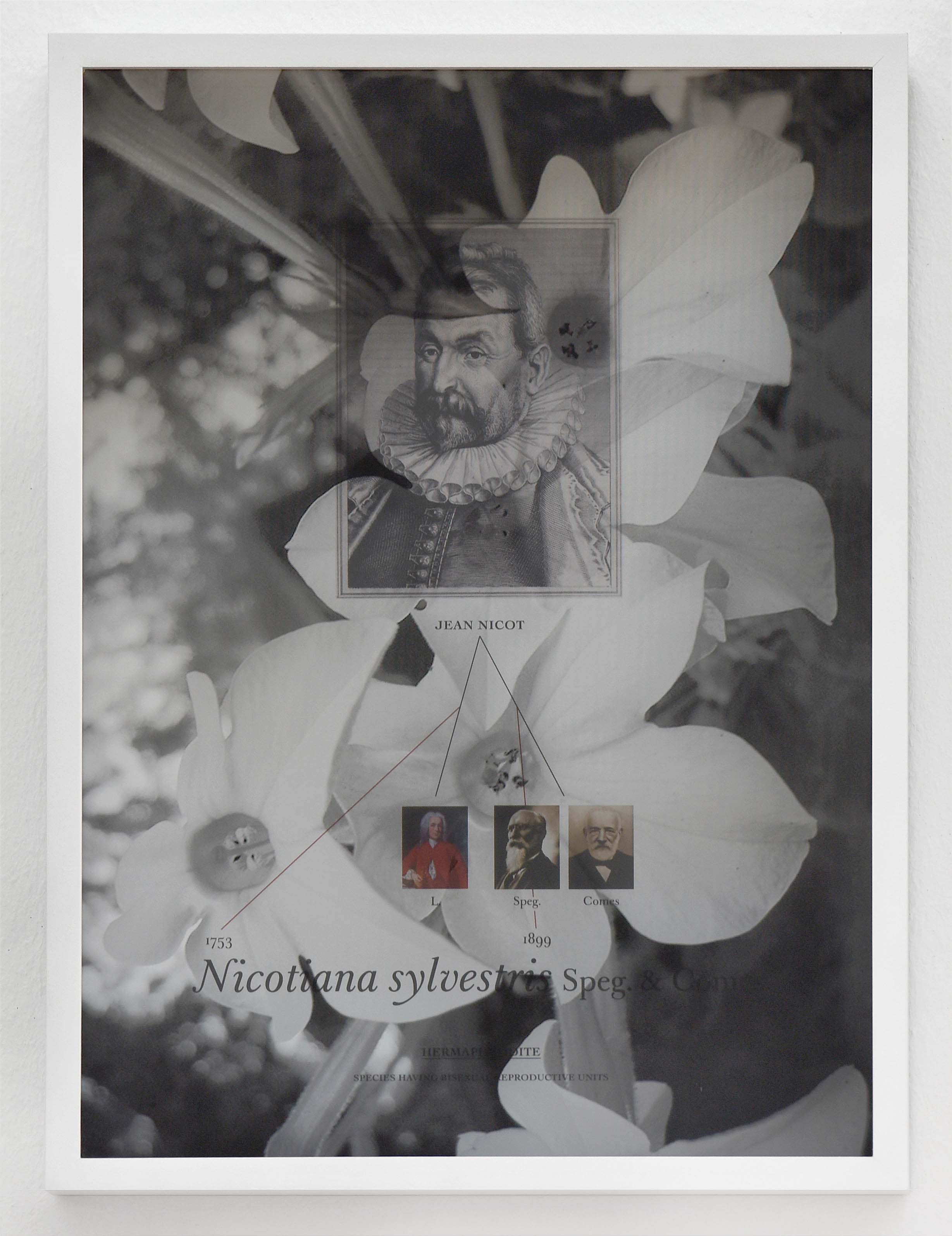

Torfs’ small frames show, in a very playful and graphical way, mimicking a genogram – a pictorial display of a person’s family relationships — how Linnaeus and his many followers retold the story of the Western elite through their well-managed naming system. They depict an imaginary community, featuring portraits of the patrons whose names were given to the 25 plants in question. The Magnolia genus for example is dedicated by Carl Linnaeus to the French botanist Pierre Magnol (1638-1715). Graphically superimposed on this “family tree” are suggestive close-ups of flowers and fruits — a reference to Linnaeus’s “sexual” classification, which is based primarily on the number and arrangement of the male stamina and female pistils.

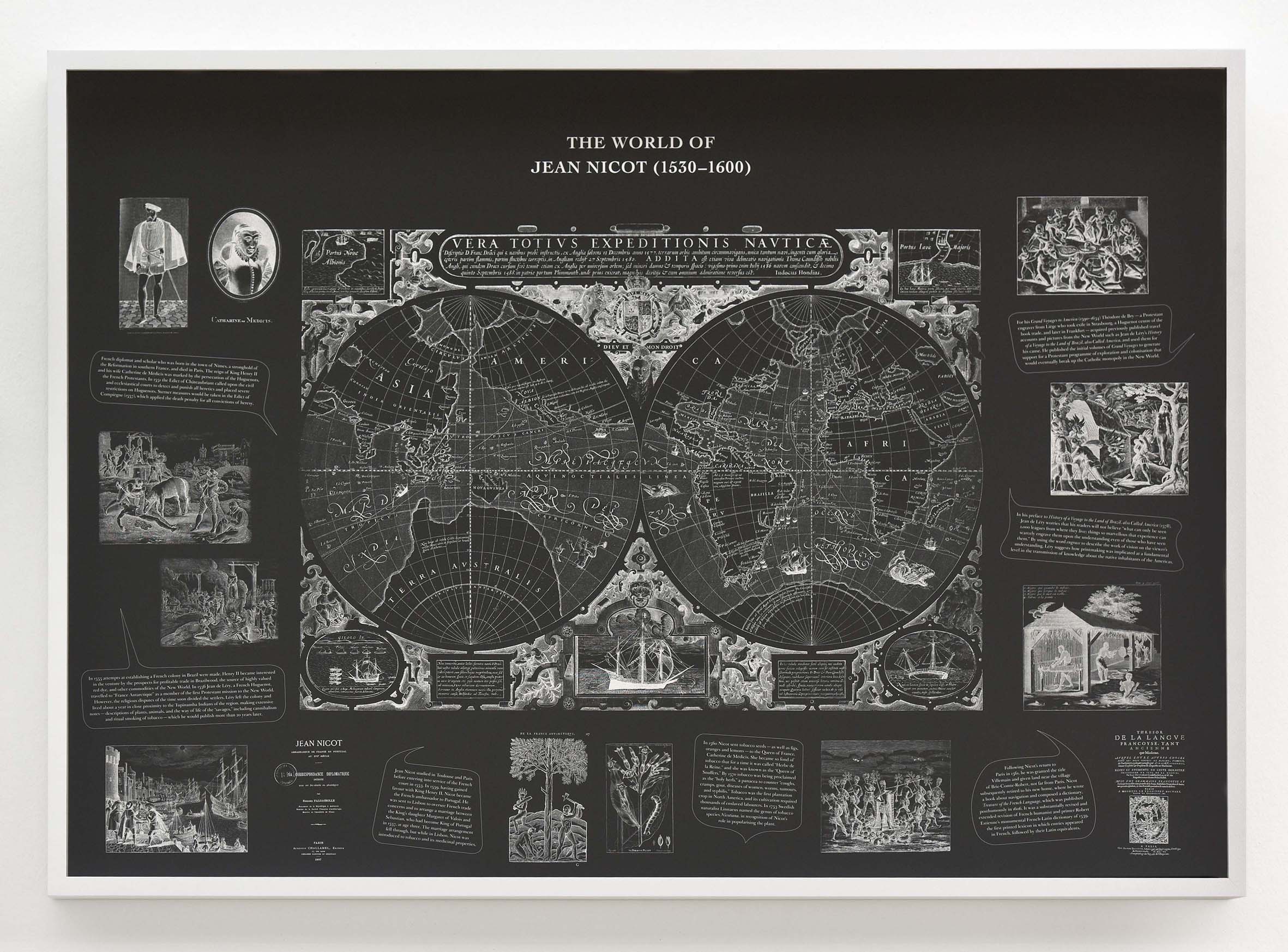

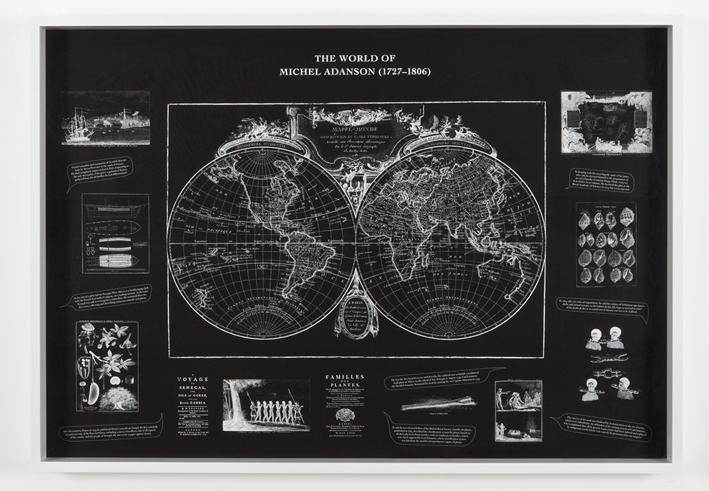

The larger set of frames spins a subtle web of interrelations between the worlds of the featured personalities, their “discoveries”, and the resulting implications for cultural history. With her fascination for the names of plants as a starting point, she further explores the “worlds” of the twenty-five name patrons, all of whom lived in the era of European exploration and imperialism. From the tropical genus of flowering plants Brunfelsia — a homage to the German scientist Anton Brunfels, who died in 1432 — to Davidia, a Chinese genus of flowering trees, which was dedicated to the French priest and naturalist Armand David, who died in 1900. The pictorial atlas before us, incorporating existing archival material, including numerous illustrations, encyclopaedia entries, and, most prominently, world maps (plot also means plan), Torfs thus offers an alternative reading of our “natural world”. Speech bubbles contain biographical information in the form of anonymous quotes, which are provided with no additional identification. Indeed, the cultural history laid bare by Ana Torfs cannot be comprehended from a single perspective. The viewer who stands before this work, experiences a sweeping view of the dark hours of world history.

- Anthony Pagden, European Encounters with the New World, 1993