Battle, 1993

For her installation BATTLE, formerly known as IL COMBATTIMENTO, Torfs chose to work with a ‘scenic madrigal’ for three voices by Claudio Monteverdi (1). The libretto of this composition was based on Canto XII of Torquato Tasso’s ‘Gerusalemme Liberata’ (1579), a romance set against the backdrop of the First Crusade. Tancredi, a Christian soldier, has fallen in love with Clorinda, a Saracen girl. The episode set by Monteverdi as a work to be acted, ‘in genere rappresentativo,’ as opposed to others ‘senza gesto’ (without gesture) concerns the encounter of Tancredi with a mysterious opponent. They meet on the battlefield, by the walls of Jerusalem, unrecognisable in their armor. They fight and the mysterious knight is deadly wounded; Tancredi then discovers that he has killed his beloved Clorinda (2). The clashing of swords, galloping horses, Clorinda’s ascent to heaven – Claudio Monteverdi made all this audible in this composition. He chose a text that explores the relationships between war and love: as a soldier storms a fortress, so does a lover lay siege to his adored one’s reticent heart: ‘Three times the knight grips the woman in his strong arms and the same number of times does she break free of those strong bonds (…) weary and panting, both must draw apart at last and draw a breath after a long labour.’ Monteverdi’s composition was first performed in Venice in 1624 but not printed until 1638, when it appeared with several other pieces in his eighth book of madrigals (written over a period of many years). Monteverdi’s introduction to the later publication declares that it was staged at the Palace of the Most Illustrious and Most Excellent Signor Girolamo Mozzenigo, his particular patron, a knight of very good and delicate taste, as an evening carnival entertainment in the presence of the entire nobility, nearly moved to tears and vociferous in their applause.

Torfs’ ‘video triptych’ allows the heads of the three performers to be shown individually, the singer of the narrative (‘il testo’, performed by Richard Jackson) face on in the middle, and the crusader Tancredi (performed by Mark Oldfield) and the pagan maiden Clorinda (performed by Zofia Kilanowicz) as pendants in profile on either side. Two of them, Tancredi and Clorinda, barely sing. The third character, the observing ‘testo’ or narrator describes the acts performed by the other two.

Torfs reduces opera to pure breathing, swallowing, vibrating, and the location of a voice in a body, to mouths that open and close. The body’s gestures are reduced to the gestures of the face and the physical act of singing. Through the complete absence of historical setting and period costumes the text regains in explosive directness. ‘The ‘blankness’ of the singers’ faces – after all, singers ‘perform’ the drama with their voices, not through facial expressions – contrasts strangely with the emotions evoked by their music, the savage action being narrated and the passion of the characters they represent’(3).

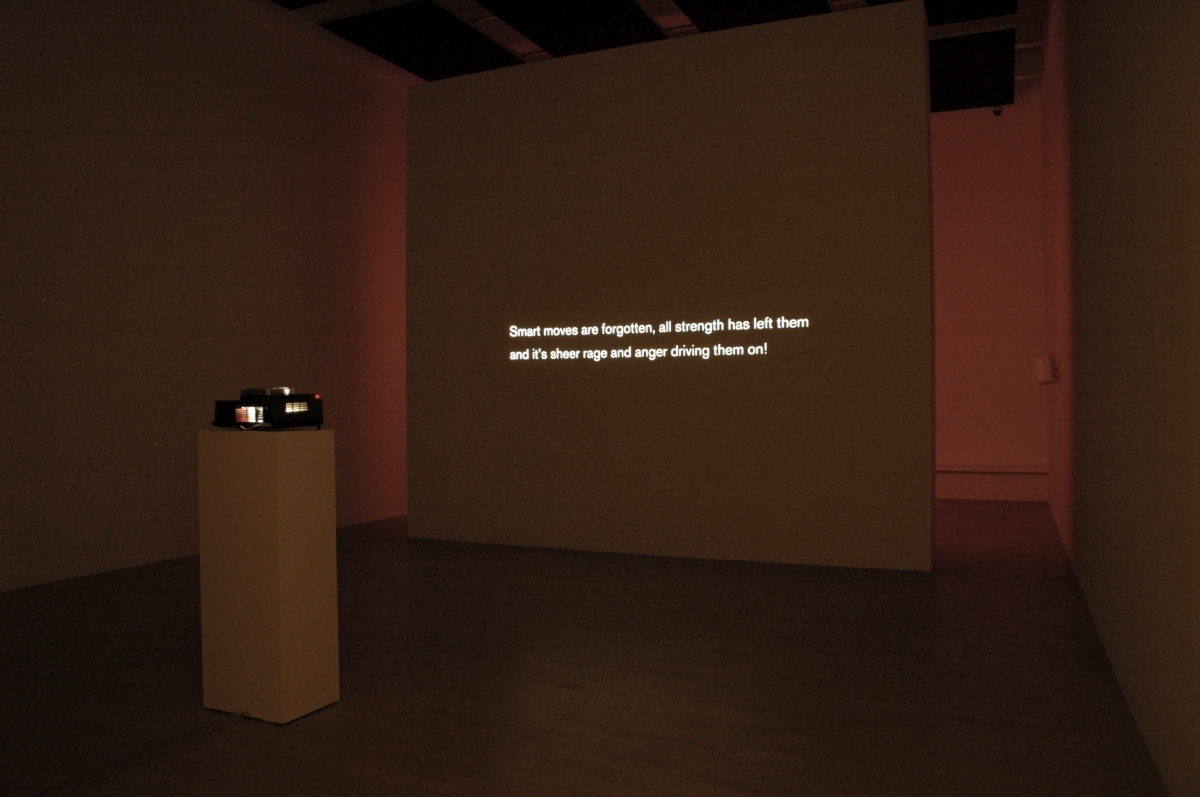

In the course of digitizing the original 1993 material in 2009, a new version emerged entitled “Battle”. Subtitles, which would usually be positioned directly in the projected image to provide an English translation of the sung Italian, now lead a life of their own in a different medium, that of a slide projection. The musical space as a temporal element connecting everything together now finds itself divided into two halves—one with the singing faces and one with the linguistic “translation” as text slides that shift according to what is sung. The sound of the slide projector further underpins the musical dramaturgy: where the action peaks, there are fast shuttling noises, whereas in the melancholy scenes the fragments of speech naturally slow down. The result is a mechanical sound composition on the basis of the mannerist dream of a possible scenic unity of instrumental sounds, singing, and gestures. In Torfs’ installation “Battle”, the modalities of this possibility change into equivalencies of sound, body, and language and their particular media forms. As a consequence, our focus on the music changes from space to space. With the triptych, it is on breathing, artistry, effort, or facial contortions, whereas in the slide space, concentration is on the sequences of words, their dynamics and mannerist audacity. (Michael Glasmeier, 2010)

1. Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda

2. Luciano Berio arranged the work in 1966 for a performance that was meant as a Vietnam War protest at the Juilliard School in New York.

3. Catherine Robberechts in ‘Impossible Portraits’, 2002