TXT (Engine of Wandering Words), 2013

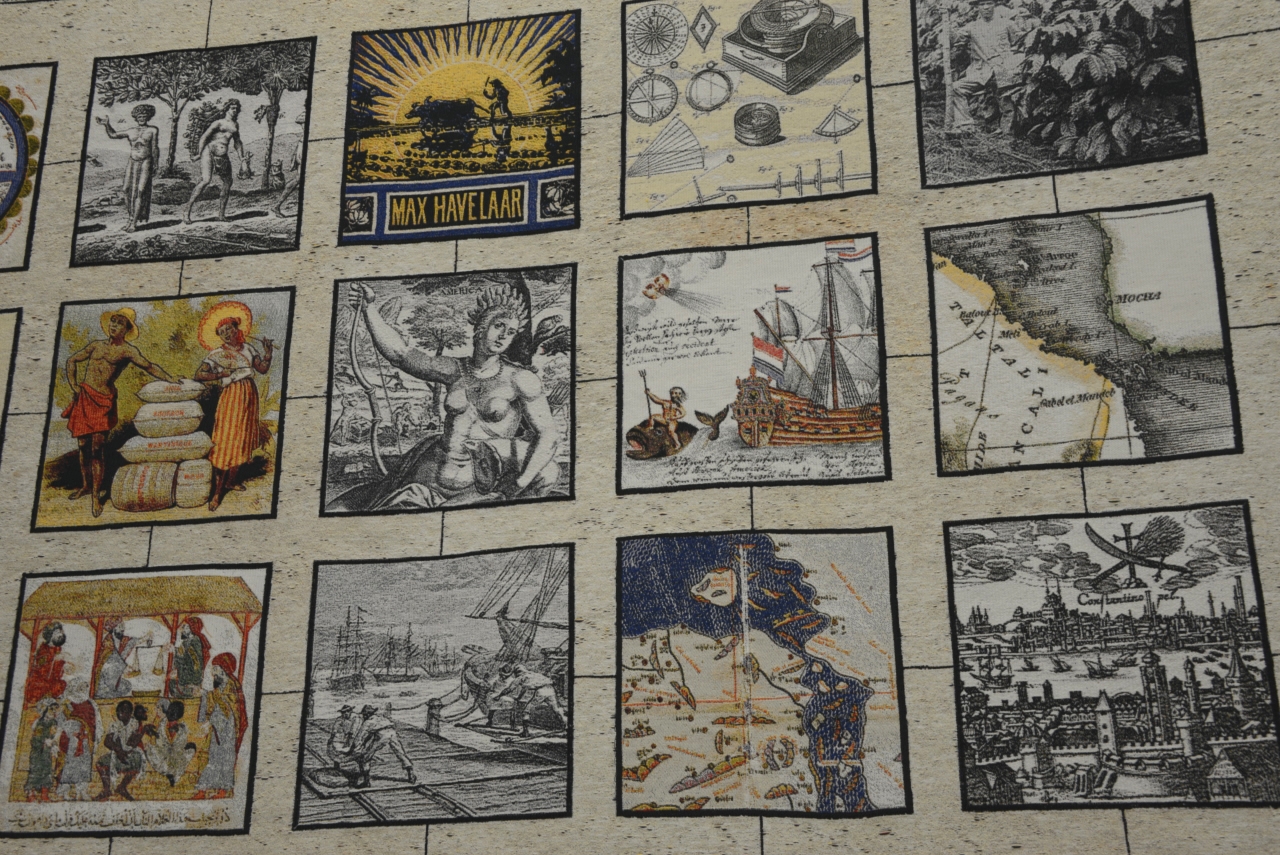

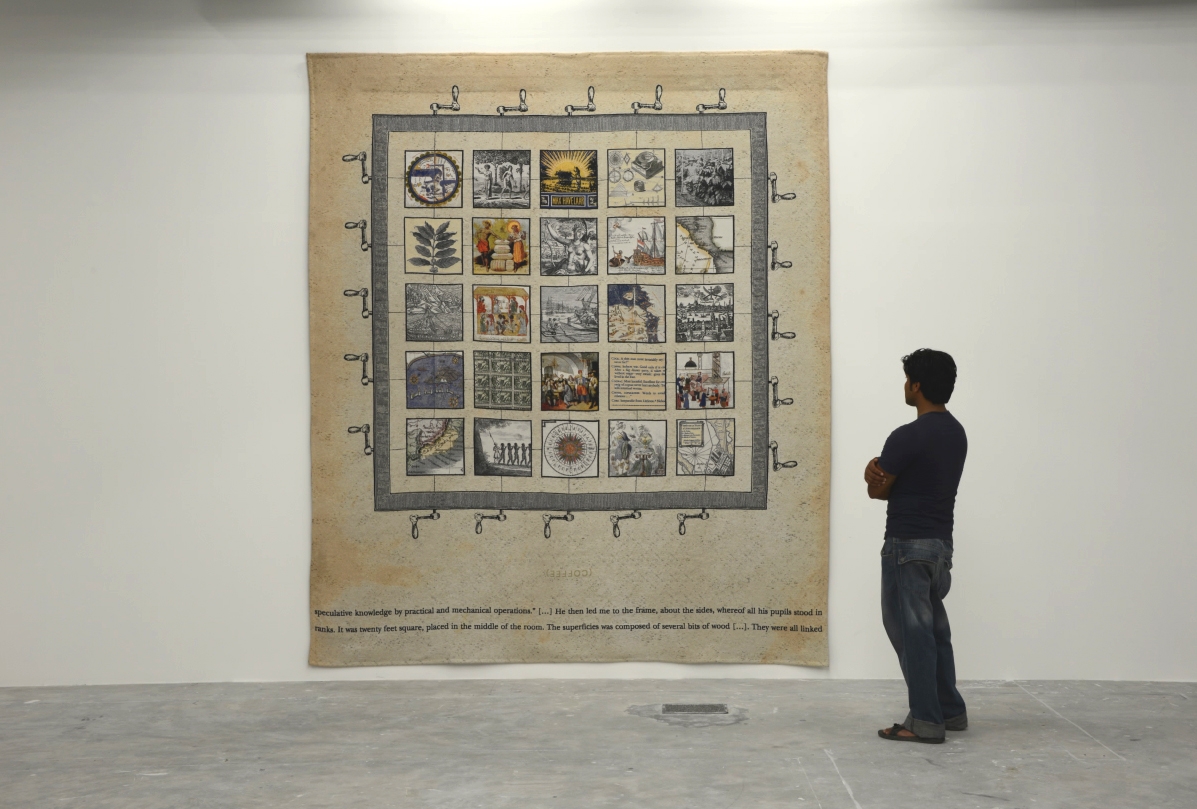

Each of six tapestries depict a strange mechanical device with squares of twenty-five different images and handles along the edges. These squares depict fragments of existing photographs, engravings, oil paintings, maps, pamphlets and book pages from various time periods. Lines connect the squares to the handles, and soon we realize that these are in fact cubes that can be turned, revealing another side, perhaps with a new image. Is this a visual dictionary? A rebus? A children’s game? An “engine of the imagination”?

The first part of the title, TXT, evokes text. Text, texture and textile all derive etymologically from the same Latin verb, texere, meaning to weave. In The Elements of Typographic Style (1992), Robert Bringhurst writes: “An ancient metaphor: Thought is a thread, and the raconteur is a spinner of yarns—but the true storyteller, the poet, is a weaver. The scribes made this old and audible abstraction into a new and visible fact. After long practice, their work took on such an even, flexible texture that they called the written page a textus, which means cloth.”

And what about the “wandering words” of the work’s title—a literal English translation of the beautiful German noun Wanderwort? Trade brings languages together. It is easier to borrow an existing word from another language than to make one up. Approximately sixty percent of the English language is borrowed. If a word is simply adopted from another language, with only little or no modification, it is called a “loanword”. In English too, Wanderworts are a special type of loanword. It is a word that spread among numerous languages and cultures, across a significant geographical area, from language to language, and it is not always possible to ascertain from which language it originated, often as a result of trade or adoption of newly introduced items or cultural practices.

It took me quite some time to decide on which “wandering words” I would focus, but I chose ginger, saffron, sugar, coffee, tobacco and chocolate. All of these words are typical Wanderworts, which sound almost the same in many languages across the world (suiker in Dutch, sucre in French, azucar in Spanish, Zucker in German, zucchero in Italian, sukar in Arabic, shakar in Persian etc.). Apart from ginger and saffron, the Wanderworts I selected are very much connected to the history of colonialism. The images selected for each tapestry are connected to the “story” of the word in question when it travelled through the world. What at first glance appears to be a playful and light-hearted work confronts us, image by image, with the harrowing consequences of international trade, which is often accompanied by colonisation, slavery and exploitation. The worlds unfolded by words is something I’m very interested in, and I made several works that deal with this fascination, such as Family Plot (2010) Legend (2009), STAIN[…] (2012) and The Parrot & the Nightingale, a Phantasmagoria (2014).

The machine, or engine shown on the tapestries is inspired by an illustration by J.J. Grandville, for the 1838 French edition of Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels. This great adventure story has amused and confused readers since its first publication, in 1726, as Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships. The book is both a parody of travel writing and a satirical exploration of politics, colonialism and human nature. On the island of Balnibarbi, Gulliver visits the Academy of Lagado, an early scientific institute. There he is given a demonstration of a giant machine, used for making sentences and books. Every turn of the handles generates series of random combinations. Swift’s invention might be the earliest example of a (fictional) contraption resembling a modern computer. During his guided tour of the Academy of Lagado, Gulliver also observes projects intended to do away with words altogether. Because words were only names for things, it was reasoned that people would be better off if they dealt with things themselves rather than with words. I placed the fragment from Swift’s book in which he describes the Engine, at the bottom of the tapestries, distributed randomly across all six of them.

These tapestries were woven on a Jacquard loom, named after inventor Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who was born to a family of weavers in Lyon, France, in 1752. His loom was the first programmable machine: It used punch cards to store complex weaving patterns in a binary format, enabling the weaving of any design of which the imagination could conceive and mechanizing a previously labor-intensive task. Jacquard revolutionized the weaving industry, and the principle of his loom is still in use today, although the automation is now computer-driven. American inventor Herman Hollerith applied the same technology to construct the first data-processing machine. In 1911, he sold his tabulating machine company to the conglomerate that later became International Business Machines, or IBM. Jacquard-style punch cards were widely used in the early computers of the 1940s to 1970s. Today, of course, these have been replaced by other storage methods.

Ana Torfs, 2012