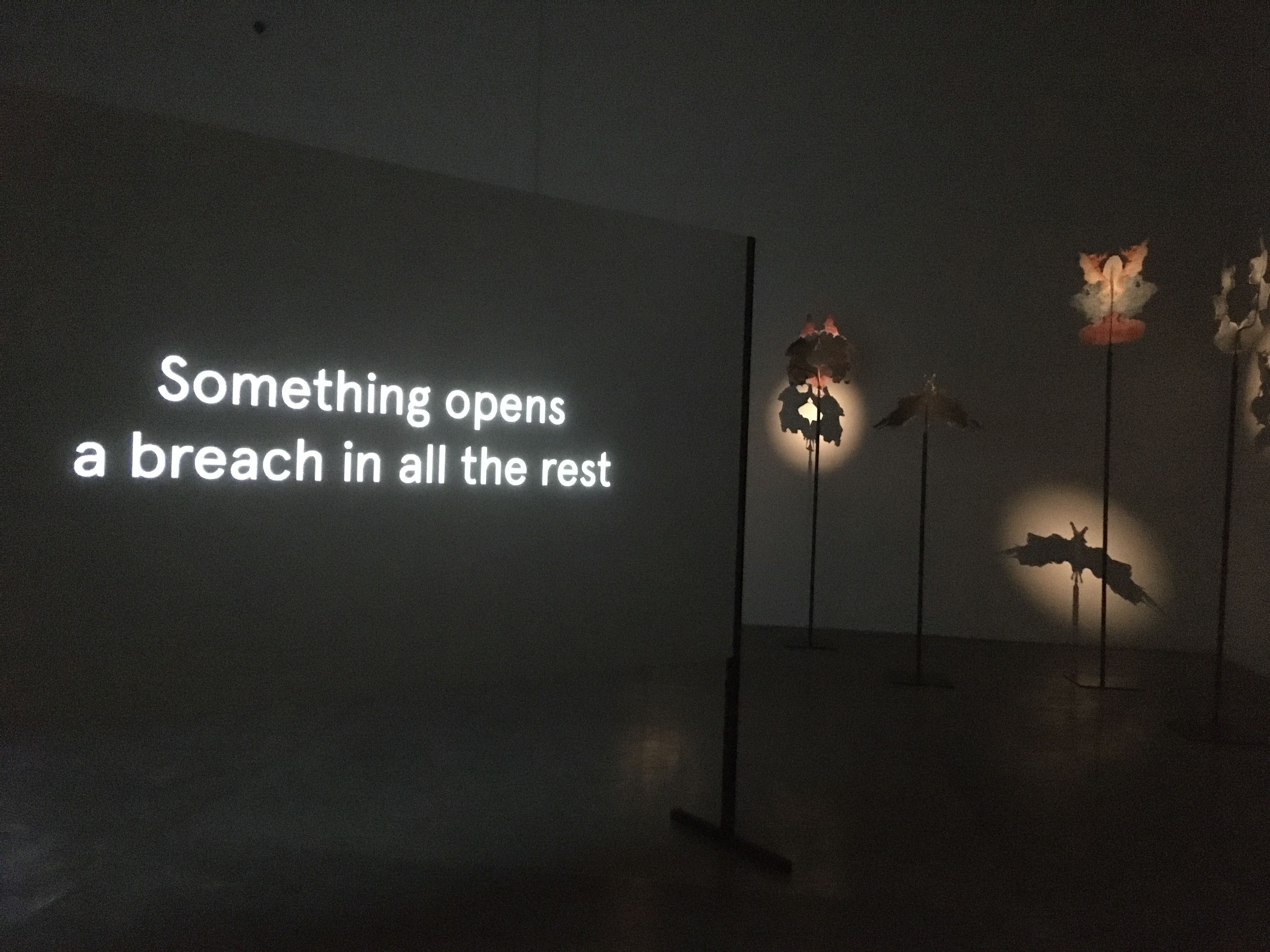

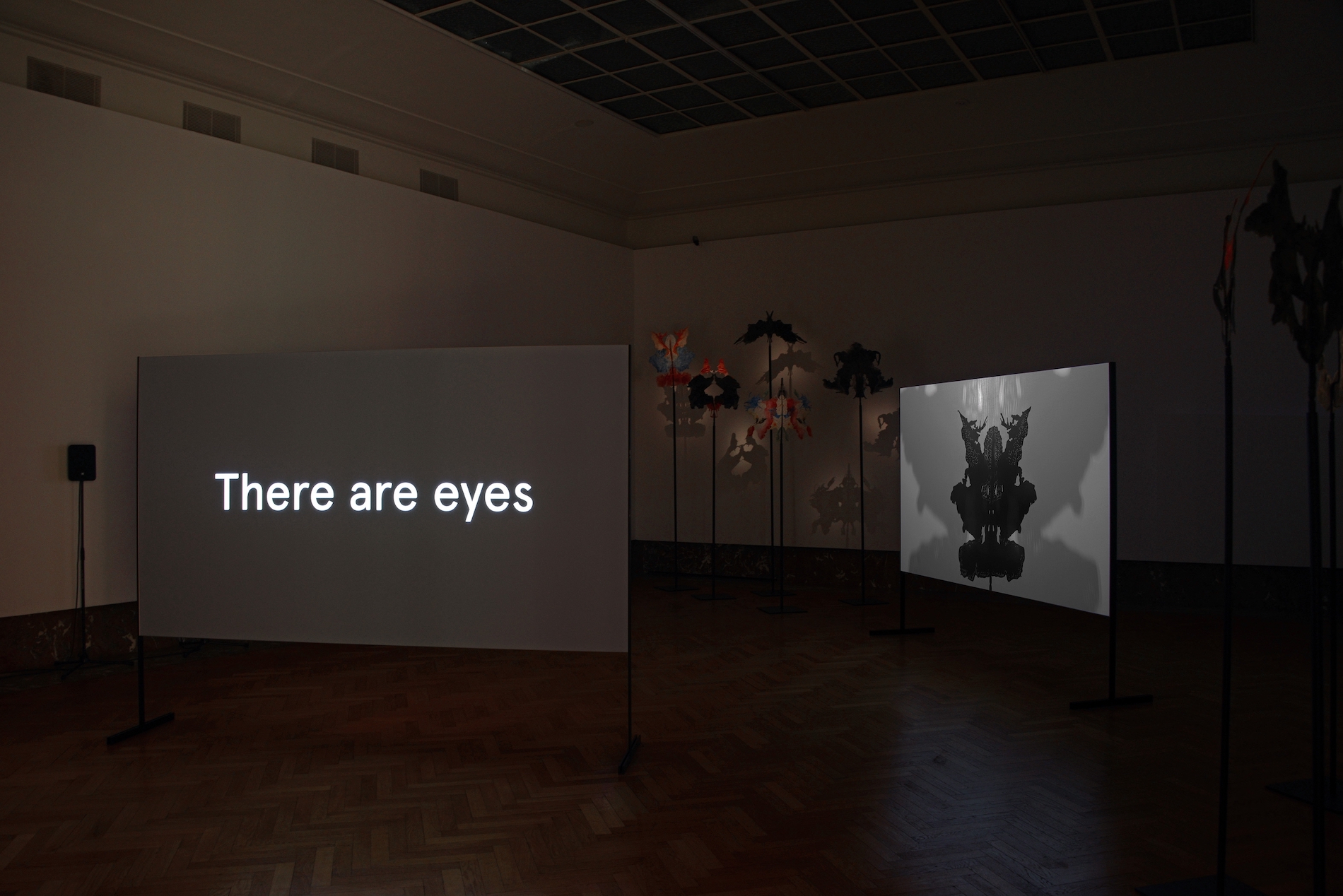

Incantations (double double), 2017

Incantations (double double)… The title of this installation sounds like a spell, but what will actually be conjured up?

According to the “Merriam-Webster Dictionary”, the word incantation derives directly from the Latin “incantare” (to enchant), which itself has “cantare” (to sing) at its root. This reminds us that magic and rituals have always been associated with chanting and music. In the “Encyclopaedia of Shamanism” (C. Pratt, 2007) it says that an incantation is a magical arrangement of words that has the power to manipulate actions. The voice is a manifestation of an individual’s power. Words charged with that power can turn into sacred forces or objects. Speaking a incantation is a way to make one’s intention an active force in the world, for better or worse.’

In the handmade shadow puppets, exhibited on metal stands, some visitors may recognize the ten iconic inkblots published in 1921 by the Swiss psychiatrist, Hermann Rorschach. The Rorschach test, a controversial psychological test, became highly popular in the USA from the 1930s, also among anthropologists during fieldwork.

The verbal instructions given by an anthropologist to a subject at the start of the Rorschach test were standardized to some degree. He would say something along these lines: “What I am going to show is a set of ten cards on which are printed inkblots, some black and white, some using colour. Different people see different things in these cards. Did you ever look at clouds and imagine what they could be? That’s what it is. I’ll show you the first card and just tell me what you see.” There were no rules for how to answer. The subject was in fact encouraged to feel that all answers were good answers. And as the subject advanced to describe what he or she saw on the cards, the examiner meticulously recorded it.

Ana Torfs became very fascinated by these Rorschach protocols from people living in every corner of the world, as noted down by anthropologists (a Rorschach protocol is the written report of all oral responses given by one or more subjects to each of the ten inkblots). Not the statistics and the classified data and conclusions to which they led, but the poetry of those words that hardly anyone apart from the scientists in question has ever read. The beauty of the Rorschach inkblot cards themselves, which continues to inspire so many artists, has also captivated her for many years.

Torfs selected fragments from various Rorsach protocols that were recorded between 1938 and 1981 by anthropologists on the island of Alor (then a Dutch colony in present-day Indonesia), in Native American Reservations, in Japan, Algeria and China, but she also included fragments from reports by Hermann Rorschach himself. Torfs became fascinated by this material, the poetry and the words themselves, as language and literature. From these protocols Ana Torfs created an English language script consisting of 120 song texts for six voices.

Torfs spent several months working on the selection and order of these strange sentences, which reminded her of Cadavre exquis (‘Exquisite Corpse’), the collaborative, chance-based game that the French surrealists used to play. Some fragments reminded her of Japanese haikai, glazed miniatures, while others seemed like concentrated short stories, flash fiction. Take for example this song, which she composed from the Rorschach test of an Apache shaman: ‘A music sign. A land underneath the water. A man is moving between animals with a stick in his hand. The butterflies are happy. The rabbit is as calm as it should be. Is the singing good or bad?’

For the recordings, six Javanese singers of different ages made musical improvisations, based on a Javanese translation of Torfs’ English script. The ten Rorschach inkblots were transformed by Javanese craftsmen into shadow puppets and brought to life in a shadow play by Nanang Hape, a young puppeteer from Jakarta.